|

|

|

Searching Donner Summit | Timeline | Map

Greg Marsden and Tom McBride reach snowshoer lost for two days.

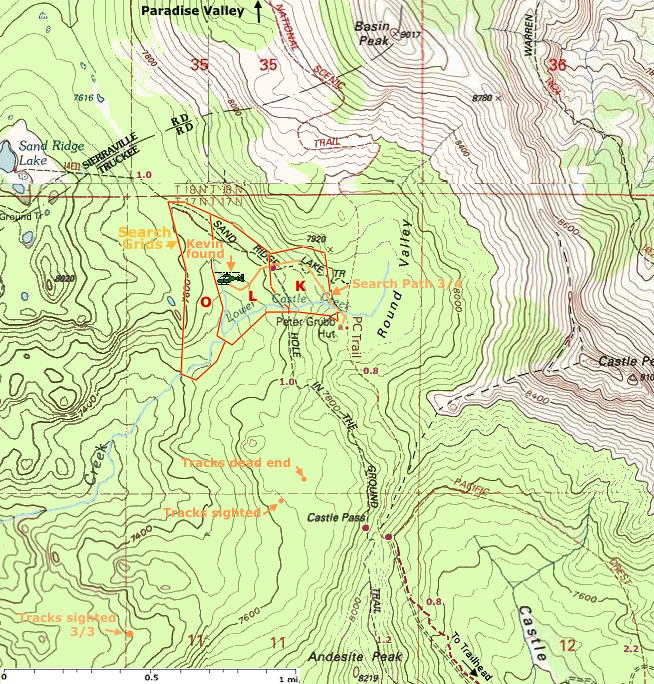

By Greg Marsden, Director Tahoe Back Country Ski Patrol When we found Kevin he was freezing, huddled in the snow and too tired to stand. No one who has participated in a Search and Rescue would dispute the power of sheer luck in these endeavors, but in Kevin's case it was also the underlying search and rescue protocols as well effective partnerships between volunteers and local officials that made that kind of luck possible. For three days, eighty volunteer searchers from various local agencies scoured the area near California's Donner Pass. A raging storm was depositing several feet of new snow, but for the Tahoe Backcountry Ski Patrol's Search and Rescue team this search was on our home ground, the winter wilderness area of the Tahoe National Forest.

Tahoe Backcountry Ski Patrol's Winter Search and Rescue team was

called out at 7:40 p.m. that evening. The Tahoe Backcountry Ski Patrol

is a volunteer organization, providing search and rescue, winter

safety, and emergency medical services in the Tahoe National Forest

and the Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest. TBSP operates a SAR team,

part of the National Ski Patrol's Far West Division, with training

based on NSP's Mountain Travel and Rescue curriculum. All training

sessions and missions are conducted under the umbrella of California's

Emergency Management Agency. In the last few years, TBSP-SAR has been

engaged with several major winter operations including a search for

two missing skiers out of Alpine Meadows, CA and a search for a lost

hiker in Southern California's San Bernadino county.

Rescuers reporting to the incident command post at Boreal Mountain

Resort that first night included Tahoe Nordic Search and Rescue,

Nevada County Sheriff's Search and Rescue, TBSP-SAR, and several other

local agencies.

Caught between the responsibility to search their gridded areas and

their inclination to follow the nearly covered footprints, Peter and

Mark chose to perform a hasty search based on the tracks as far as

they could. It appeared that Kevin had found a snowmobile trail but

followed it in the direction away from the trailhead.

Ground teams searched the area throughout the daylight hours on Wednesday, but steady snowfall and low visibility hampered the search effort and prevented any hope of air support. By nightfall, no further clues had been found but the storm was finally beginning to let up. It was our missing person's second night out and the forecast called for a low of 4 degrees Fahrenheit.

Search and rescue is often a mechanical operation. Teams are sent out to "clear" individual grids created on a map; each subsequent day's searches are based on the ability of the previous teams to clear those grids. The speed at which the search is initiated matters: the search area expands with each day the missing person can travel away from the point they were last seen. For each grid it was important to check for the possibility that the lost person was either responsive or unresponsive, and searchers are asked to assign two distinct probabilities of discovery for each grid. With two feet of new snow having fallen since Kevin was reported missing, our chances of finding a unresponsive subject were very small. Our personal GPS units were configured to track our search progress and to display the coordinates of each grid area. At the end of the search, the GPS log of our paths would be downloaded and used to plan the next day's search operations. Having been briefed and given radios and dispatch sheets, we emerged from the incident command center and headed out to the snow cats. Several of these tracked vehicles, smaller version of the vehicles used to groom ski resorts, were parked around the incident command center. Like the previous night's NSP search team, Tom and I were traveling fast and light with a minimum of gear and planning to depend on Tahoe Backcountry Ski Patrol's backcountry caches for our overnight supplies. Our team crammed into the back of two snow cats and soon we were cruising through an area normally closed to motorized travel; exceptions are made when life is in jeopardy. Twenty bumpy minutes later we arrived at the base of Castle Pass, a short 200 foot climb up to the ridge overlooking the Peter Grubb hut. This was as far as the snow cats could go: the incline was too steep to proceed beyond this point. At 2 a.m. Thursday morning, our ten searchers from Contra Costa and TBSP-SAR began the climb up Castle Pass and along the ridge toward the Sierra Club's Peter Grubb Hut. One Contra Costa SAR team member, Derek, was also on backcountry ski gear and he joined us climbing up and over the main ridge overlooking Round Valley. The seven other searchers traversed around on snowshoes. We skiers descended quickly towards the hut, spreading out and attempting to give extra coverage to additional grids as we headed towards our main search region. The Peter Grubb Hut lies near the center of Round Valley, flanked from north to east by the imposing sights of Castle Ridge and Basin Peak, and to the south and west by a gentle downward sloping forest filled with complex terrain including ravines. It was the ravines to the west that we would search that night. The key to a grid search is keeping your partners close enough that you can see and communicate with one another, but far enough away that you are able to reliably cover a large amount of ground. Already we had noticed that the two feet of fresh snow was impeding our travels. We decided to have the skiers cover the perimeter of the search areas, while the snowshoers fanned out and attempted to cover the interior sections. With the three-quarter moon overhead, the other searchers and their tracks were clearly visible without headlamps. The search area was a mostly flat region with a gentle downslope away from the hut, abutting a large meadow and an imposing buttress of cliffs. The deep snow was impeding travel, and the snowshoe teams switched to moving single file to cover ground more quickly. By 6 a.m., our team of skiers had barely managed to cover the perimeter of the first of three search areas and we decided to pause our search activities and return to the hut for some rest. We were asleep as our heads hit the mattresses. Search and rescue personnel should be equipped to spend the night out if necessary, and to self-rescue or self-evacuate. While Tom and I had backcountry caches of equipment to rely upon, Tom decided to forgo the trip to the cache and napped under a pile of down jackets. Despite our exhaustion, we were all awake again after just three hours, readying our gear by 9:30 a.m. The sun was shining and the untouched, snow-filled valley was radiant -- this was the break in the storm everyone had been waiting for. If our missing person was going to be found, we told ourselves, today was the day. Another team of TBSP-SAR rescuers, patrollers Eric Chesmar and Ted Hullar, inserted that morning on the other side of Castle Pass looking for evidence that the missing hiker might have made it over the pass and then succumbed to fatigue or injury. Their morning progress was significantly impeded by the considerable avalanche danger and they spent much of the morning navigating around unstable, overhanging cornices before returning to base.

The high walls of Castle ridge blocked our radio traffic with the

incident command base, so most of our communications with dispatch had

to be via cell phone.

We were instructed to bide our time at the hut,

and told that either a helicopter or another search team would be

arriving soon with a cache of new radios and a repeater to relay our

communications back to SAR base.

Our team's objective for the day was to pass through our recently searched areas and then follow a drainage out to nearby Paradise Valley. Overhead, we could hear the thump of the helicopter rotors as the two aircraft assigned to air support searched the area. Less than an hour into our resumed search we noticed the smaller helicopter, a California Highway Patrol A-Star B3, hovering close by. The CHP helicopter had received the coordinates of a potential sighting from the Chinook, and the pilots went in for a closer look. Kevin had signaled the aircraft by tying a corner of his space blanket to a ski pole, and waving it while sitting on the edge of a small clearing. The highway patrol aircraft confirmed the sighting of the subject, but could not land due to low fuel and lack of a suitable landing zone. We were the closest rescue team and they relayed his coordinates to us as they headed out to a nearby airport to refuel and return for the rescue. Not bothering with the GPS, we moved quickly to follow the bearing towards the coordinates and soon could hear Kevin yelling and whistling. Tom was the first ground rescuer to make contact with him; it was now 12:30 on Thursday, about 44 hours since he'd been reported missing. When we arrived, Kevin was huddled in the snow. Tom and I, as ski patrollers, assumed responsibility for Kevin's medical care. Derek from Contra Costa assumed field command and orchestrated the communications relay and evacuation logistics. While privacy constraints prohibit a detailed description of Kevin's condition or our assessment, we had time to wrap Kevin in blankets and sleeping bags, complete a full assessment and begin care by the time the helicopter refueled and returned about 45 minutes later. We provided insulation including gloves, ensolite pads and sleeping bags, assisted by a nurse practitioner from El Dorado's Search and Rescue who arrived 15 minutes later. As the rescue helicopter returned, the weather was starting to close in again and the pilot was anxious to get the patient evacuated and the aircraft back to safety. With hypothermia a real possibility, the decision was made not to hoist Kevin via "screamer suit", but to try to land the helicopter and backboard him for a gentler helicopter extrication.

Kevin had wandered around for about two miles during his ordeal, eventually trying to backtrack to the Peter Grubb Hut and ending up less than a half-mile away. Disoriented by the sloping descent along his path, he missed his target and settled in the ravined area downhill from the hut where he built a tiny shelter in a snow drift. The shelter was barely large enough for his head and shoulders and left the rest of his sleeping bag exposed to the clear night sky. At the closest point during our previous night's search, our team of skiers passed within 200 meters of his shelter. What kept him alive was his sleeping bag and his resourcefulness, staving off dehydration by tying his water bottle to a string and lowering it through a hole in a snow bridge to a creek to get water. During the cold, clear night he even lit a propane lantern inside his sleeping bag to keep warm, but quickly realized the fumes would not be healthy. Though he credited survival television shows for his resourcefulness, and they did keep him alive, his crude attempts at shelter construction on level ground highlight the benefits of competent instruction in backcountry safety practices. Not long after Kevin lifted off we were again socked in by snow and low clouds. With no hope of an air evacuation for our rescuers, Tom and I led a complement of thirty search and rescue volunteers on the trek back up to the Peter Grubb Hut, then up and over Castle Pass to the phalanx of waiting snow cats. More than eighty searchers participated in this incident, with search and rescue resources from Nevada, Contra Costa, Placer, El Dorado, Washoe, and Marin counties, the California Air National Guard, and our Tahoe Backcountry Ski Patrol Search and Rescue Team. Tahoe Backcountry Ski Patrol Search and Rescue is looking for qualified ski patrollers in Northern California to join our search team. Find out more by visiting tbsp.org/sar or emailing sar@tbsp.org. Timeline: Tue. 3/2 - Kevin leaves Peter Grubb Hut ahead of his friends who plan to catch up with him on the hike back to the trailhead. He misses the trail to Castle Pass and veers off to the west. After arriving at their cars, his friends waited for several hours before calling the local Nevada County Sheriff. 7:40 PM TBSP SAR called 10 PM Search starts Some tracks are found along a snowmobile trail going the wrong direction. Tracks are soon covered by heavy snow. A search of the area found more tracks which were again lost. At some point Kevin turns around to head back to Peter Grubb hut. Wed. 3/3 - Searchers return in early morning More ground teams searched the area throughout the daylight hours but, steady snowfall and low visibility hampered the search. Snow stops by nightfall having dropped 2 feet of new snow. Forecast calls for a low of 4° wed night. 12 AM More searchers head out to search grid areas K, L & O NW of Peter Grubb hut. Thu 3/4 6 AM Searchers head back to Peter Grubb hut for some rest Later that morning searchers head out again to search an area north of the hut A helicopter spots Kevin and radios his coordinates to the search team as the helicopter headed back for gas. Tom reaches Kevin at 12:30 PM Rescuers are warming Kevin up as the helicopter returns to take him to the hospital  zoom out | Google map of search area | Map page w/ satellite map Acknowledgment: Some photos courtesy Contra Costa County Search and Rescue

Links:

|