Religion

Religion

Religion and Politics

Religion and Politics

Mainline Declne

Mainline Declne

Don's Home

Religion

Religion

Religion and Politics

Religion and Politics

Mainline Declne

Mainline Declne

|

Source: Source: WSJ article below.

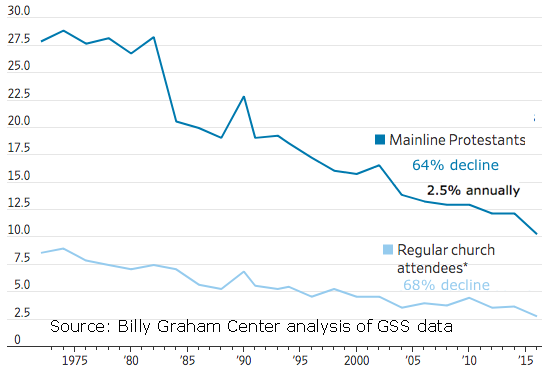

See also Christian Denominations Politics in the Pews: Anti-Trump Activism Is Reviving Protestant Churches--at a Cost - WSJ By Ian Lovett May 4, 2018 10:51 a.m. ET Christ Church in Alexandria, Va., a historic Episcopal church, hasn't been a particularly political congregation. It has welcomed Democratic and Republican presidents. George Washington and Robert E. Lee were members. Stone plaques commemorating them adorn a wall. Then last year, Richard Spencer, the leader of a white nationalist organization, rented office space in Alexandria. Several parishioners organized protests outside his office, which became bimonthly events. The church released a written statement denouncing white supremacy, and later decided to remove the plaques honoring Washington, who owned slaves, and Lee, who led the Confederate Army. "We just have to keep standing up," said David Hoover, 61, a member of the church who helped organize the protests outside Mr. Spencer's office and is encouraged by the church's sharper political tone. That same foray into politics outraged other members. After the announcement that the plaques would be removed, at least 30 people quit the congregation, according to current and former parishioners, including some who had been there for decades. "There is no sanctuary at Christ Church, just a battleground," Riki Ellison, 57, a former NFL player, wrote to fellow members of his family's decision to leave. Political activism is reshaping what it means to go to mainline Protestant churches in the Trump era, with tensions bubbling between parishioners who believe church should be a force for political change, and those who believe it should be a haven for spiritual renewal. Galvanized by opposition to Trump administration policies, these congregations, which typically are theologically liberal and historically white, are turning themselves into hubs of activism. For some congregations, that shift has prompted a surge in attendance--especially among young people--something mainline Protestant churches haven't seen in decades. Liberal churches are organizing rallies, taking on racial issues and offering sanctuary to undocumented immigrants. Some clergy have returned to the front lines of protests, where they are playing more prominent roles than any time since the Vietnam War. These moves have alienated conservatives, or worshipers who think politics has little place in church. Pastors pushing their congregations toward activism acknowledge their efforts could hasten the demise of a mainstay of American life: the apolitical mainline church where Republicans and Democrats sit comfortably side-by-side in the pews. But they contend it is the best way to follow Jesus ' example--and maybe the only way to save churches whose membership and influence have been in decline for half a century, having been overtaken by their evangelical counterparts. "If we're not going to stop the wall and the deportations, then I don't think we're following Jesus," said the Rev. Kaji Dousa, pastor of Park Avenue Christian Church in Manhattan. "We're just getting people in church, and that's not interesting to me. The point of following Jesus is that you move and you do." When Ms. Dousa took over in the fall of 2016, weekly attendance hovered at around 15 people. The church, a 107-year-old stone- and stained-glass building, is affiliated with Disciples of Christ, and with the United Church of Christ, one of the most progressive and activist mainline denominations. The previous pastor had largely eschewed politics, members said. Ms. Dousa began preaching about refugees and has accompanied immigrants living in the country illegally to their check-ins with Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers. In one sermon, she likened the U.S. under Mr. Trump to Weimar Germany. Now the church is bustling nearly every day of the week. About 200 people recently gathered at the church for a rally led by two survivors of the Parkland, Fla., school shooting, who advocated stricter gun control. Regular Sunday attendance, meanwhile, has jumped to about 100--including an influx of young people who hadn't attended church in years, or sometimes ever. Danelle Bain, the 28-year-old daughter of a pastor, joined Park Avenue Christian Church last year after nearly a decade away from organized religion. "Churches have upped their activism this year, because there's been a call for it," said Ms. Bain, who took part in a recent protest against deportations that the church helped organize in Washington Square Park. "Those churches are really drawing the millennial crowd." Wading into politics hasn't gone as smoothly for her father, a pastor in Stillwater, Okla. For three decades, the Rev. John Bain led politically mixed Disciples of Christ congregations, where Democratic and Republican party leaders sat side-by-side in the pews. Keeping the peace was never difficult, he said, until last year. Trump supporters assailed him for being too critical of the president. At the same time, liberal members pressured him to engage more directly with politics. The church created a special ministry for immigrants, which outraged some members who saw it as taking a political stand. Several longtime members left the church. Attendance has dropped from around 220 a week in 2016 to 180 on average now. He said he wishes he could do more to "be the hands and feet to this world," but is afraid for his livelihood "with one of my kids still in school." "I've had some pretty ugly conversations after worship," he said. He now steers clear of mentioning Mr. Trump during his sermons. Until the 1960s, mainline Protestants were the dominant religious force in the U.S. Since then, their numbers have been in steep decline and they now make up only 10% of the population, down from nearly 30% in 1972, according a Billy Graham Center analysis of data from the General Social Survey, a federally funded research project.

Mainline Decline

Mainline Protestants as a percentage of all Americans They have a long history of advocating for social causes, including an active role in abolitionism in the 19th century and the civil-rights movement in the 20th. Around the time their numbers began to decline, many churches withdrew from front-line political activism and focused on less-polarizing work such as helping with food distribution for low-income people. Liberal clergy leaders say they recognize the risks of politicizing the pews, but see an opportunity to reinvigorate the spirit of the mainline church. "Church buildings and church membership are declining, and part of me says, 'Thanks be to God,'" said Jason Chesnut, a Lutheran pastor in Baltimore who advocates for more church engagement on social issues. "Lots of churches are trying to hold on to what we had in the 1950s and 1960s. I'm not interested in continuing what has often been a glorified country club." Many denominations haven't released recent membership numbers. Pastors at mainline churches around the country, however, noted an increase in church attendance. The United Church of Christ reported a decline in membership nationwide in 2017, but at a slower pace than the past several years. A number of individual churches in the denomination--including 14 of 18 surveyed in the Southwest--said attendance and rose during Mr. Trump's first year in office. "People are wanting our faith communities to take a stand," said Bishop Dwayne D. Royster, pastor of Faith United Church of Christ in Washington, D.C., and political director of the PICO National Network, which has helped organize churches offering sanctuary to immigrants. "Those that do are going to see growth. Those that don't are just going to eventually become more marginalized." At Christ Church in Alexandria, the congregation is struggling to heal its rifts. Rev. Noelle York-Simmons, who took over as church rector in late 2016, said she doesn't shy away from political themes, but nor does she talk politics to the exclusion of other issues--from death to divorce--that affect her parishioners. Clergy from Christ Church of Alexandria, Va., arrive for a service in the aftermath of a shooting of Republican lawmakers at a baseball practice in 2017. Clergy from Christ Church of Alexandria, Va., arrive for a service in the aftermath of a shooting of Republican lawmakers at a baseball practice in 2017. "I like to preach with the newspaper in one hand and the gospel in the other," she said. "But I'm not going to do that every week, particularly when the congregation is feeling pretty beat up." Around 80 newcomers joined the congregation last year, according to church records--nearly three times as many as left. Church officials say they aren't sure of the reasons. "What people are saying to us is that they're joining the parish for the same reason they have always joined our parish: the loving community, the incredible outreach, serving people locally, serving people abroad," said Ms. York-Simmons. The church has around 1,800 members, according to records, with Sunday attendance at around 480. Lt. Gen. Ed Soyster, 82, a retired Army officer who describes himself as politically centrist, left the church late last year, along with his wife, after nearly two decades. As an usher in 2008, he escorted President George W. Bush to a pew during a visit. He said the decision to take down the plaques, which came after a deadly clash over Confederate statues in Charlottesville, Va., was symbolic of an increasingly political tenor. "It's just an indication of the changes that are taking place in that church, and whatever the biased left agenda is," he said of the plaques. Sermons, he added, would often have "no mention of Christ or anything. They were political. They were about racial equality and various things that should be done." Charles Andrae said the increasingly political tenor is exactly why he left Christ Church last year, where he had been a member for about 30 years. "I go to church to hear the word of God and help where I can," said Mr. Andrae. "The political rhetoric in church--that's no place for it." Diana Butler Bass, an Episcopalian and author of books on American Christianity, said fights over how and whether to engage politically are "taking place in every congregation at this moment." She once worked at Christ Church in Alexandria, and said she was proud of the church's efforts to combat white supremacy, even though it is not "a front-line liberal activist congregation." Historically, she said, taking a political stand is a risk. In Memphis during the civil-rights movement, she said many of the largest mainline churches waffled. Those that took a stand in favor of civil rights often shrank or closed. "If mainline churches do the right thing, no matter the cost, maybe there will be nobody left in 25 years," Ms. Bass said. "But those churches will have followed their calling--that's what matters." No decision has been made about where the plaques honoring President Washington and General Lee will go once they are removed from the sanctuary. For now, they remain on either side of the altar. |